With reference to Baudelaire, Perec and Ellard

Defined by the Tate Gallery as being “the effect of a geographical location on the emotions and behaviour of individuals”, psychogeography is a way of thinking which has grown on me with enormous fascination this past year. The term psychogeography was coined by a Marxist theorist named Guy Debord in 1955 in order to explore how different places make us feel. Heavily involved with Letterists and Situationists, Debord was a key figure in the revolutionary philosophy to art and literature which centred around Paris in the late 1950s and 1960s. A pivotal inspiration to Debord’s way of thinking was the character of a flâneur, invented by French poet Charles Baudelaire, which in layman terms can be described as an urban wanderer. In the eyes of Baudelaire, a flâneur was typically a man of the upper class echelons who would wander the urban realm with no particular purpose other than to be a perceptive observer of urban life (the historic female counterpart being a ‘passante’). Since the term’s genesis, amongst the creative circles the flâneur has come to be associated with urban planning insofar as this mode of experiencing an urban space allows for the closer connection to be made between the place itself and the emotions one feels from such a space. The concept of a flâneur was instrumental to Perec, and to Ellard more recently, such as the observer-participant dialectic provided a more prominent discourse within the urban planning community regarding the nature and function of space. Baudelaire’s critical depiction of the flâneur inspired urban theorists to define and class urban spaces alongside sociological and psychological theories and hypotheses.

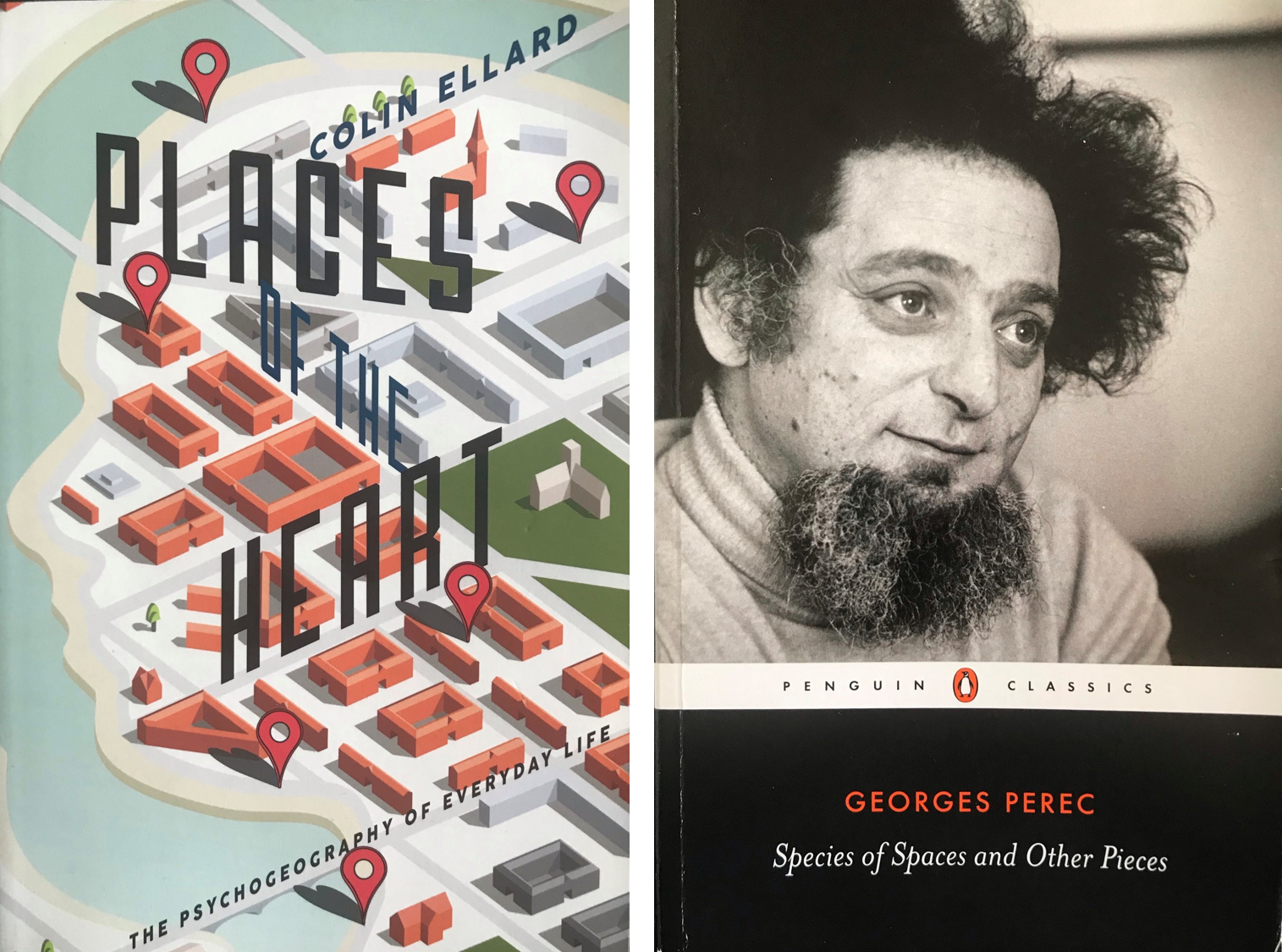

While the peripatetic navigation of the urban fabric underpins the phenomenological facet of psychogeography, the term can encompass a more wide ranging multi-sensory way of viewing our urban spaces. In Colin Ellard’s book ‘Places of the Heart’ he repeatedly makes connections between the ways humans and animals make habitual decisions. Due to his profession as a neuroscientist, Ellard is always trying to translate and codify our urban landscape into psychological terms which parallel the scientific world. Via a reference to German ethologist Niko Tinbergen’s argument regarding habitat selection which states, “the crucial element for an animal was to see and not be seen”, Ellard explains how often in ‘grand old public squares people will most often sit and relax at the edges of the space rather than towards the centre’. In my experience of open public spaces I can certainly agree people are much more likely to sit on the fringes of the space where they have the primal vantage point of being able to surveillance the space without necessarily being in a position of open vulnerability from other people’s gazes. As such, from an urban planning perspective, placing benches and seating areas along space edges will sate the primitive component of the human mind. One could however make the argument that in the 21st century context, such explanations for spatial preference (seating placement for example) could be restricting our urban experience to outdated principles.

Ellard’s aforementioned book primarily focuses on the connection between the human psyche and design. This connection results in a form of feedback loop insofar as a specific natural form evokes feelings of, for example, tranquillity in humans. The next stage of design involves an attempt to recreate these natural forms in urban design to facilitate the same reaction – a continuous process mapped in the swathes of biomimicry on show in our urban landscape today. On the other hand, in his text ‘Species of Spaces’ Georges Perec aims his insightful focus beam on matters more relating to a greater level of appreciation for what he calls the ‘infra-ordinary’ i.e. the seemingly mundane details that bypass our attention. However, Perec argues these details are often overlooked and taken for granted – on many an occasion he encourages the reader to take a moment away from the rush of modern life and to simply appreciate and analyse the very spaces we currently reside in.

In a section of the text labelled ‘The Apartment’, Perec critically analyses the functionality of an apartment space. He puts it beautifully in this following passage:

“It seems to me, in any case, that in the ideal dividing up of today’s apartments functionality functions in accordance with a procedure that is unequivocal, sequential and nychthemeral. The activities of the day correspond to slices of time, and to each slice of time there corresponds one room of the apartment.”

In our day to day lives we often fall into these rigid patterns of living and it becomes too easy for rooms to become a “purportedly single, pseudo-modular space” whereby each room has a set function in our lives and thus malleable pieces of space are reduced down to singularly functioning areas. The apartment can be easily divided into not only spaces of function but also spaces of time – accentuating the dependency of interior layouts on our habitual activities. This can often be useful in facilitating an efficient completion of daily tasks, but these predetermined layouts and room attributions are set on a wider societal basis (grounded in economic margins and social class systems); largely every house will have the same basic number of rooms (excl. bedrooms/bathrooms) yet not every person/family perhaps has the need for all those prescribed rooms – often resulting in either empty or misused pockets of space in a vast number of modern houses/apartments.

One does run the risk of straying too far into the hypothetical here, but Perec implores for a greater level of imagination and individuality in designing our rooms. He poses the question, why not divide our rooms not by function but by senses – inducing the creation of rooms like a ‘gustatorium‘ or a ‘auditorium‘, or even a ‘smellery‘. The idea of a wider sensory experience within the home is greatly explored by Ellard in a section denoted ‘Places of Affection’. At the renown MIT Media Lab, the CityHome project aims to create a living laboratory where an apartment is wholly interactive and responsive not only to one’s hand movements but also moods and emotions via regulatory sensors and trackers. Ellard describes the idea as having the apartment in essence play the role of a responsive/interactive butler. Through projects at his own labs in the University of Waterloo, Ellard has worked with computer scientist and artist Daniel Vogel on the possibilities of incorporating large interactive display panels in architecture. The home becomes sentient and acts responsively and accordingly to your varying needs and emotions, somewhat applying a more modern and productivity focused application to Perec’s creative hypotheticals. Ellard writes how “a more sentient home, by learning your habits and having a window into your physiology could be even more proactive in helping to care for you”. As such, the differences between Ellard and Perec are perhaps more clear now; Ellard is promoting a wider-sensory experience to facilitate a more efficient and healthier life, Perec is promoting the same vision but as a creative and unique means of breaking the status quo.

Perec also proposes the enjoyable concept of rooms not based on circadian rhythms, but on heptadian rhythms (a division of time centred around a seven day/one week cycle). The apartment would then have seven rooms, with Perec’s nomenclature for these rooms being a: “Mondayery, Tuesdayery, Wednesdayery” etc… you get the idea. He makes the extremely valid point that “Saturdayeries and Sundaryeries” already exist in the form of weekend homes, and a summer villa used only for a month or two would have equal usage compared with a room dedicated to be used only on a single day of the week. Each room could be of a different thematic style with Perec writing:

“The Mondayery, for example, would imitate a boat: you would sleep in hammocks, swab down the floor and eat fish. The Tuesdayery, why not, would commemorate one of Man’s great victories over Nature, the discovery of the Pole or the ascent of Everest.”

From a 21st century standpoint where we have become indoctrinated by a) functionality b) productive efficiency and c) money, such inceptions of course seem wild and vastly problematic. But if you remove the shackles of modern corporate life, surely like Perec envisages, there are an array of more fun and unique ways of dividing up the space we live in.

While Perec is perhaps not the most common name in the psychogeography world, some of the later parts of ‘Species of Spaces’ fall more into its realm. In the section labelled ‘The Street’, Perec creates a series of physical exercises one can take to indulge their senses with the joys of flânerie. Relating to writing down things of note that one can see when out and about, a statement by Perec that particularly caught my eye was “Nothing strikes you? You don’t know how to see.” Regardless of how blunt this conclusion may seem, it certainly resonated with me as in our current fast-paced world we sometimes forget how to look. Perec says one “must set about it more slowly, almost stupidly. Force yourself to write down what is of no interest, what is most obvious, most common, most colourless”; from constant exposure and exhaustion to this practice one can develop a more replete understanding of the workings of their urban space. Psychogeography and flânerie are all about curiosity, asking questions like: why do the streets carve the space like that, where is that person going to, why is this street tree-lined but the next one isn’t etc. The key is to examine and question not only the obvious but also the details that get overlooked by the ordinary person. Perec describes a sense of childlike inquisition and fascination that comes from merely sitting on a bench for a few hours and deconstructing the urban fabric in front of you.

Next time you are in your house, observe how much or how little your rooms and products are designed to maximise your efficiency and engagement. Next time you are wandering through an urban space, why not take a moment to stop and engage with it; ask questions of it, analyse and observe its users, decode why it works or why it fails to properly function.

Ask why, become a flâneur.